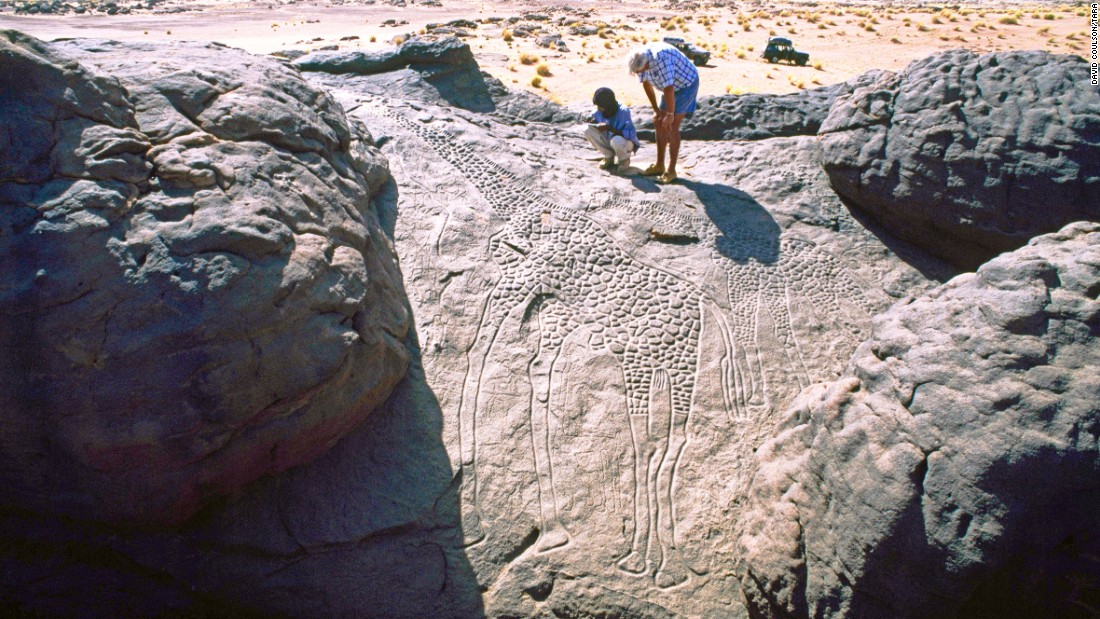

For thousands of years, giraffes have captivated people with their long necks and stooped gait. Rock carvings, estimated to be 9,000 years old, in the Sahara desert in northern Niger, reflect the first human contact with giraffes.

Some of the most prominent known examples of Saharan rock art are the Dabous giraffe, found north of Agadez in Niger. It is not clear who carved these figures, but the Tuaregs may have created them.

In the Dabous district, rock inscriptions spanning several thousand years are common; More than 300 are known, ranging in length from the very small to the life-size depictions shown here.

Possibly from 5000 to 3000 BCE. C., each giraffe is carved into a gently sloping rock. The choice of location may have been a deliberate attempt to capture oblique rays of sunlight so that surface engravings are visible at certain times of the day. Human figures representing local hunter-gatherers are drawn to scale below the giraffe. The naturalism, perspective and attention to detail are outstanding.

The climate of Africa was much wetter during the period when the inscriptions were made than it is today, and the Sahara region was a green grassland that supported abundant wildlife.

Other examples of contemporary rock art in the area depict elephants, antelopes, zebu cattle, crocodiles, and other large grassland animals, although giraffes appear to be particularly important to hunter-gatherer groups of animals in the area.

Under the auspices of UNESCO, the Bradshaw Foundation is tasked with coordinating the Dabous conservation project, in association with the Trust for African Rock Art.

The conservation project involves molding the carvings to create a limited edition of cast aluminum, one of which will be donated to the city of Agadez, near the archaeological site, and another will be located at National Geographic headquarters in Washington DC.

Another element of the preservation project was to drill a water well in the area to support a small Tuareg community that would be responsible for guiding tourists to the Dabous site. In the heart of the Sahara lies the Tenere desert.

‘Tenere’, literally translated as ‘where there is nothing,’ is an arid desert landscape that stretches for thousands of kilometers, but this literal translation has its ancient meaning: for more than two millennia. For centuries, the Tuareg operated a trans-Saharan caravan trade route connecting major cities on the southern edge of the Sahara via five desert trade routes to the North African coast.

Dabous Giraffe Rock Art Petroglyph one of the best examples of ancient rock art in the world – two life-size giraffes carved into the rock and facing the Tuareg? Life in the region now known as the Sahara has evolved over the millennia, in various ways.

Concrete proof of this ancient occupation can be found at the top of an arid outcrop. Here, where the desert meets the slopes of the Air Mountains, lies Dabous, home to one of the world’s finest examples of ancient rock art: two life-size giraffes carved from stone.

They were first recorded in 1987 by Christian Dupuy. A subsequent field trip organized by David Coulson of the Trust for African Rock Art attracted the attention of archaeologist Dr. Jean Clottes, who was struck by its importance, due to its size, beauty and technique.

Two giraffes, a large male before a smaller female, are carved side by side into the eroded surface of the sandstone. The larger of the two stands over 18 feet tall and incorporates a number of techniques including scraping, smoothing, and deep contour engraving. However, the signs of deterioration were clearly evident.

Despite its remoteness, the site was beginning to receive increasing attention, as these exceptional carvings began to suffer the consequences of both voluntary and involuntary human degradation. The petroglyphs were being damaged by trampling, but perhaps worse than this, they were being degraded by Grafitti and fragments being stolen.

The obvious answer is to preserve the giraffe carvings for their artistic significance, but also for their place in the classical African context. The president of the Bradshaw Foundation, Damon de Laszlo, considers that “The obvious answer to this is to try to preserve them, not only for their artistic significance, but also for their place in the classical-African context.

The Sahara is greener and how this relates to our “Human Journey” Genetic Map. “

This preservation would take the form of creating a mold of the carvings and then casting them into a durable material. The point of this is twofold. Now is the time to get the mold because the carvings are still, barely, in perfect condition, and by making the importance of the carvings known, their value will be realized and their protection will be prioritized.

By chance, Michael Allin’s ‘Zarafa’ publication had been published the previous year, describing the fascinating story of a giraffe from the Sudan that was driven across France in 1826: the Dabous giraffe was yet to arrive. France almost two hundred years later, but in a slightly different way.

One of the main goals of the Bradshaw Foundation is to preserve ancient rock art, but with a project of this size and nature, we clearly need permission from both UNESCO and the Niger government.

“”

Furthermore, it is important to ensure that the project is carried out at the grassroots level, with the full participation of Tuareg custodians. Ultimately, future conservation considerations had to be met and for this reason a well was drilled near the site to provide water to a small group living in the area, a member of the community.

That will act as a regular guide: to indicate where to mount the cantilever, where the petroglyphs can best be seen without walking on them, and to ensure that the steel is not damaged or lost.